A guide to surface roughness and roundness instruments

From handheld roughness gages to high-end interferometers, there’s a vast array of instruments available to measure roughness and roundness. But not all instruments are equal. Knowing the strengths and limitations of your gage can help avoid measurement errors that lead to expensive mistakes on the shop floor.

Measurement instrument manufacturers offer systems with many different options and price points. To give a general comparison, we’ll look at:

- Geometry: whether the instrument is capable of measuring roughness, waviness, and/or form/contour/roundness

- Features: whether the instrument is limited to roughness on a flat surface, or whether it can measure texture and/or shape on curves, on edges, inside bores, around and along shafts, etc.

- Part Size: dimensional limits on the size of the component that can be measured

- Vertical Range: the largest, measurable vertical departure

- Vertical Resolution: the finest measurable vertical step

- Relavtive Cost.

Roughness gages

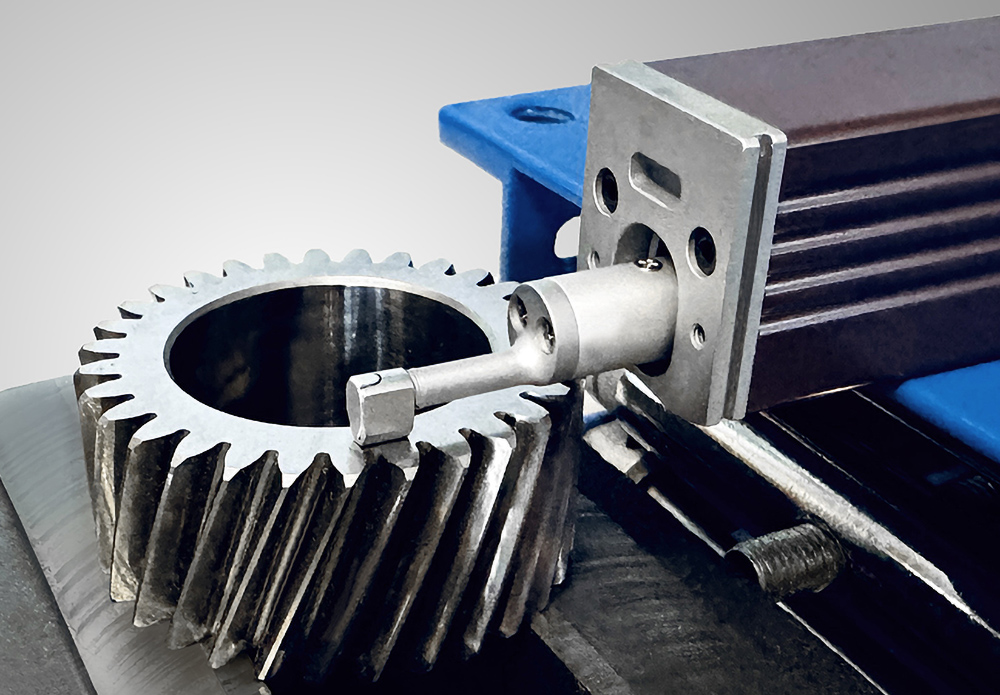

Roughness gages (surface roughness testers) are handheld, stylus-based instruments that measure roughness on relatively flat surfaces. Because they are small and portable, these gages can measure roughness on large components, assemblies, or stock. Handheld roughness testers are inexpensive, easy to use, and provide fast measurements with little setup.

Most handheld gages include a “skid” which rides along the surface, providing a reference point (datum) from which surface heights can be measured. The skid reduces the gage’s sensitivity to vibration by mechanically coupling the test piece and instrument, and it also protects the delicate stylus. However, because the skid rides over larger surface features, it effectively filters out those longer wavelengths, so the gage can only sense roughness wavelengths.

A “skidded” roughness gage. Courtesy Digital Metrology Solutions.

Skidless stylus instruments

Skidless stylus instruments can measure larger vertical departures than skidded systems. Relatively inexpensive, portable, and easy-to-use, skidless gages can measure roughness on curved and angled surfaces, and some instruments can make partial arc measurements on curved surfaces. An internal datum provides a reference, enabling traces up to many millimeters in length to acquire waviness wavelengths and to provide a larger sampling for assessing roughness.

The ability to measure roughness, waviness, and partial arcs makes skidless gages appropriate for applications such as bearing races, where both shape and texture are critical. Skidless gages, however, cannot typically measure geometric dimensions such as bearing race radius, slopes, or complex forms.

Because skidless gages are more susceptible to vibration, they require more isolation than skidded instruments. The exposed stylus is also more prone to damage from contact with steps or sharp edges.

A skidless stylus measuring surface roughness.

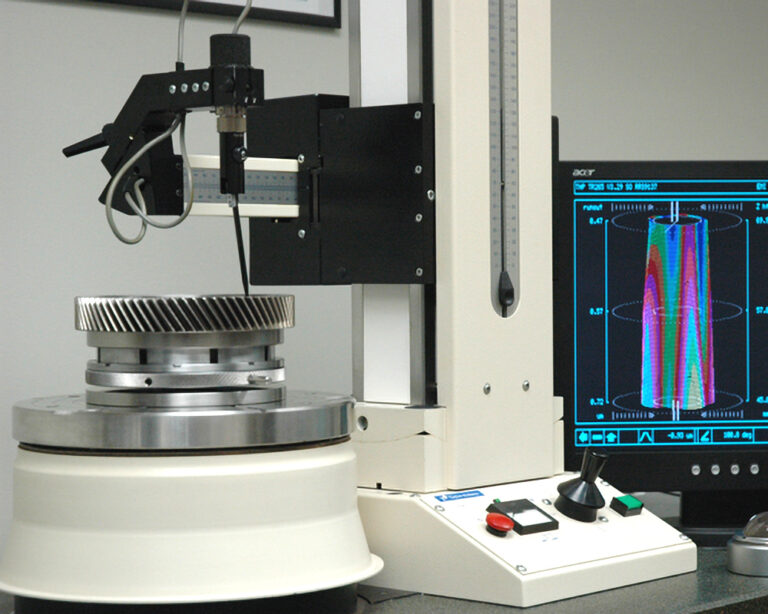

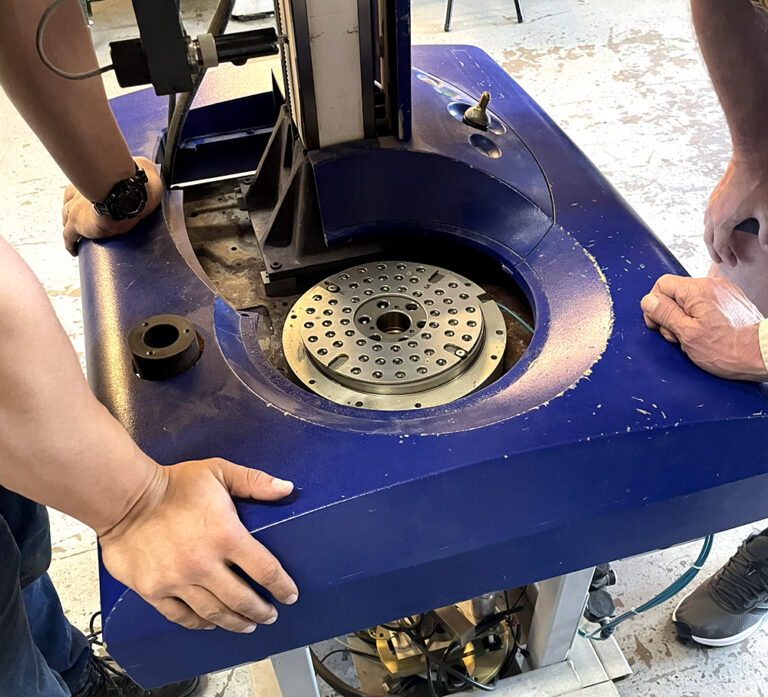

Contour gages

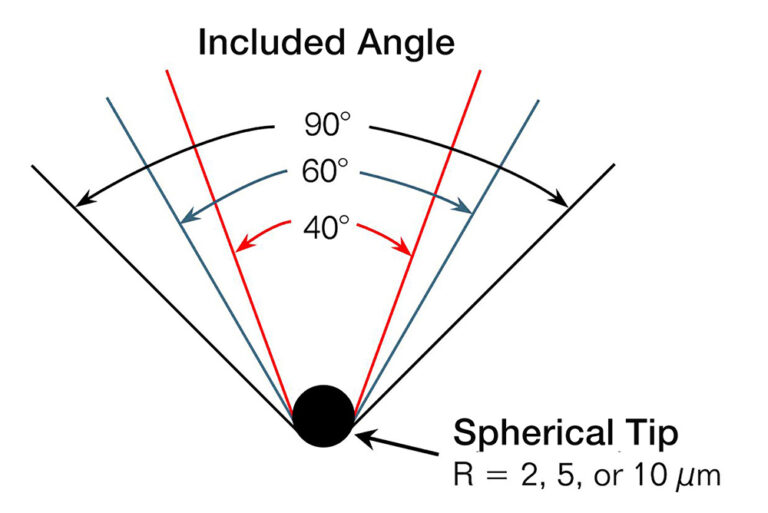

Contour stylus gages are designed for measuring larger scale contour/shape/form and features such as blends, arcs, corners, thread root radii, etc. Contour tips typically have a 20µm or 25µm radius, making them robust for measuring larger features but incapable of measuring finer roughness.

Some instruments have interchangeable heads and software for measuring either roughness or contour. The ability to switch between these domains can be cost-effective for labs that measure a wide range of parts and features; however, the setup required to switch frequently can limit throughput.

Because vibration can be impactful for these instruments, they are typically mounted on rigid posts attached to vibration-isolated bases. This arrangement limits the size of the component to be measured, laterally by the stage size, and vertically by the height of the column. System cost typically increases with the size of the column (e.g., 450mm, 700mm, or 1m) and the accompanying precision datum, as well as the type of staging.

Inductive instruments

An inductive measurement pickup (LVDT) measures changes in inductance caused by the proximity of the test surface. Inductive pickups are more precise than the piezo-electric transducers typical of entry-level stylus instruments, and they enable better vertical resolution (e.g., 15nm–30nm). High-performance inductive instruments may achieve sub-nanometer resolution; however, these higher resolutions may not always produce meaningful data. A small step height may appear as a fuzzy square wave, for example.

An inductive instrument can measure texture, small arcs, slopes, straightness, and even larger scale form, though vertical range may be limited (typically 1mm for a standard length stylus, 2mm for a 2X length stylus). These instruments offer good performance for applications such as small optics and roller bearings where both texture and small curvature are critical for function.

Laser-based instruments

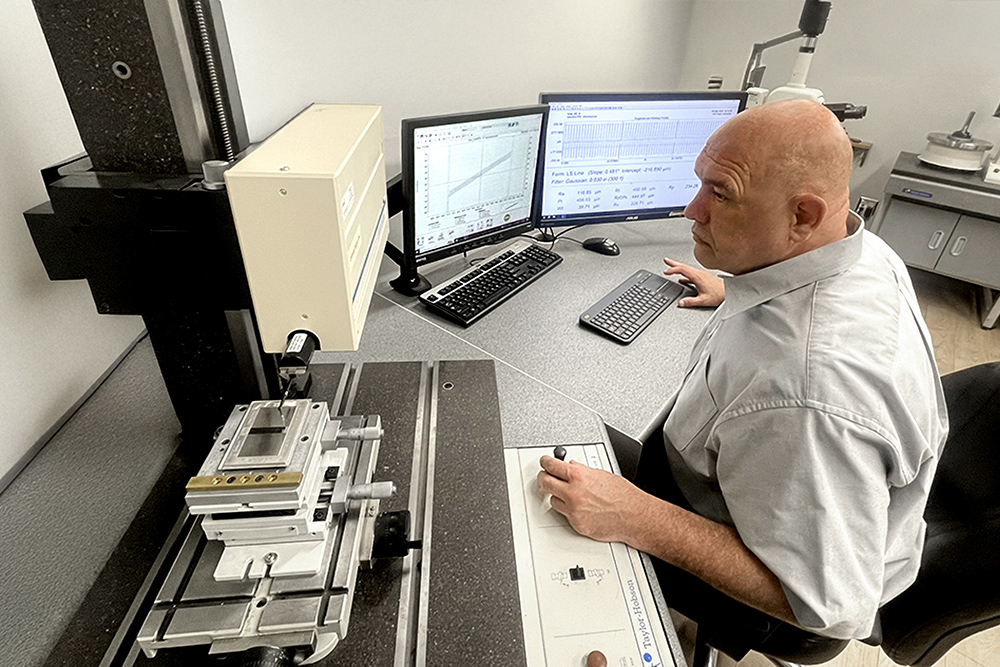

In a laser-based pickup, an internal interferometer precisely measures the stylus position. Laser-based instruments can achieve resolutions as low as 10nm over a larger range than an inductive system (up to 6mm for a standard 1X length stylus tip).

Laser instruments can measure texture, dimensions and form, including aspheric form. Applications include bearings and raceways, optics, and semiconductors.

Some systems include software to acquire and assemble multiple, side-by-side traces into a 3D surface map. Other systems employ “phase grating interferometry” (PGI) transducers, extending vertical capability to 12mm (1X length stylus) or more, with resolution as low as 0.2nm.

The cost of laser-based systems increases with features, range, and resolution. Most systems offer a range of software options to support particular applications, which can also increase the cost.

Measuring roughness with a laser-based gage.

Optical instruments

Optical instruments rely on the properties of light for non-contact measurement of surface roughness and shape. Optical measurements are typically made over an area rather than along a single 2-dimensional trace. This areal/3D ability provides excellent accuracy for roughness measurements and helps highlight aspects of texture that cannot easily be described by a single trace. For example, hills and dales can be completely characterized in 3D; in 2D, peaks and valleys may be reduced, and the actual highest/lowest point of any feature is rarely captured.

Optical instruments can capture roughness with sub-nanometer resolution, making them exceptionally useful for applications such as optics and semiconductors. Areal/3D measurement also makes it possible to determine such surface characteristics as the volume of fluid that can be retained on a surface for lubrication or printing.

Optical instruments, however, have several potential limitations for production measurement:

- The measurement size is typically small vs a stylus trace.

- The instruments typically require more setup and a longer learning curve.

- Most optical systems require significant vibration isolation.

- Most optical instruments are based on rigid stands which limit the size of the component to be measured.

- Surface features such as spheres, bores, grooves, and low-reflecting or scattering surfaces return insufficient light to the sensor, making it challenging to measure them accurately.

CMM

Coordinate Measurement Machines (CMMs) provide accurate geometric measurements in a broad range of industries. Some CMMs include an optional roughness measurement probe with a skidded stylus, skidless stylus, or non-contact optical sensor. The probe can provide roughness measurements on surfaces with average roughness greater than a few microns; however, most CMMs are incapable of measuring finer roughness scales.

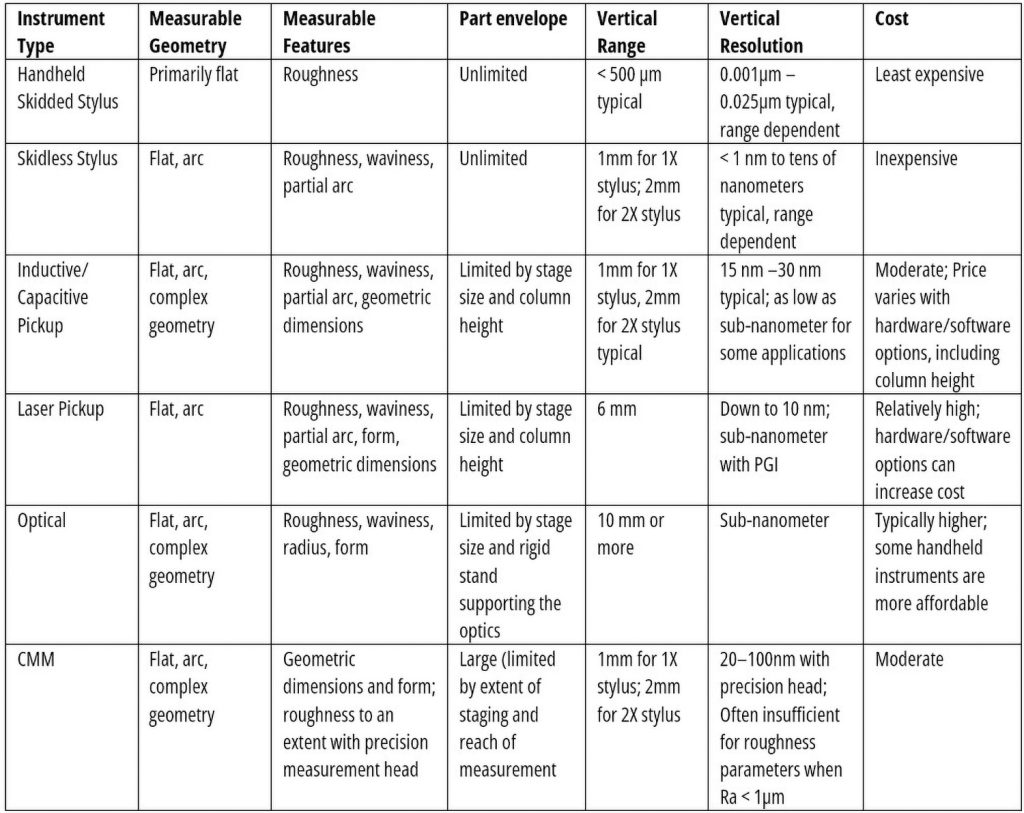

The following chart summarizes the relative strengths of these various measurement technologies.

The choice of instrument for a particular measurement will depend on these factors and many others, including the volume of parts to be measured, required tolerances, etc. While many instruments can measure texture or shape to one extent or another, the instrument must be capable of measuring the wavelengths that matter for the part’s function, with sufficient resolution and accuracy, and within budgetary constraints.